Happy 50th Birthday To Franklin, Peanuts’ First Black Character — The Story Of His Creation, Debut, And Impact

Posted at 8:00 pm on August 1, 2018 by Sarah Quinlan

https://www.redstate.com/sarahquinl...r-the-story-of-his-creation-debut-and-impact/

Fifty years ago, American cartoonist Charles Schulz introduced his first black character, Franklin, in his beloved and popular Peanuts comic strip.

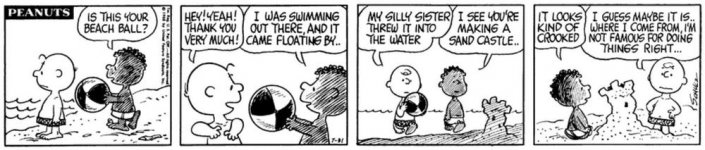

Perhaps the most moving aspect of Franklin’s debut strip was the immediate simplicity and normalcy of the two boys’ friendship. After Franklin returned Charlie Brown’s lost beach ball to him, the two built a sand castle together, with the pure innocence that only children possess — thus presenting the friendship of a white boy and a black boy as entirely natural and acceptable.

In truth, Franklin made his debut during a time period of widespread racial tension in the United States; he was introduced on July 31, 1968, just months after the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and the violent and deadly riots that followed King’s death.

The idea of Franklin arose, in part, because of King’s death. Just eleven days after King was murdered in April 1968, a white teacher in Los Angeles wrote to Schulz, among other syndicated-strip cartoonists, to urge him to include a black character.

In her letter, Harriet Glickman noted that mass media such as cartoons carry a “tremendous importance in shaping the unconscious attitudes of our kids.” She therefore requested that Schulz introduce a black character in order to “help change those conditions in our society…which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate, and violence”:

Schulz responded within two weeks, telling Glickman he appreciated her suggestion but was concerned about “patronizing” black readers:

Undeterred, Glickman continued to urge integration; during their two months of correspondence, Glickman even included letters from black friends who supported the idea, to assuage Schulz’ fears that he would offend black readers.

One of Glickman’s friends, Kenneth C. Kelly, wrote that a black Peanuts character would both “ease my problem of having my kids seeing themselves pictured in the overall American scene” and “suggest racial amity in a casual day-to-day sense.”

Then, on July 1st, 1968, Schulz told Glickman that a comic strip during the last week of July would be a “first step” regarding the inclusion of a black character.

“I have drawn an episode which I think will please you,” he wrote her.

Glickman’s suggestion and integration campaign had finally succeeded. The Peanuts circle of friends now included a black child.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone liked that the comic strip portrayed a black child among white children.

Schulz admitted he received criticism for depicting Franklin as he would a white child, such as when Franklin and Charlie Brown invited the other to their houses and again when Franklin was pictured sitting in class alongside Peppermint Patty:

But Schulz wouldn’t back down. He’d previously had to fight to include Bible passages in the 1965 television special A Charlie Brown Christmas, so he was familiar with taking a stand on issues he believed mattered, regardless of who might take offense.

However, it wasn’t just the negative reactions from white readers and editors that Schulz had to contend with.

Schulz was open about his concerns that, as a white man, he could not write about race properly or adequately capture the black American’s experience. As he had told Glickman, he worried about appearing condescending to black readers.

“I’m not an expert on race, I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a little black boy, and I don’t think you should draw things unless you really understand them,” Schulz said in one interview in 1988.

“I wasn’t sure I can do it frankly,” Schulz said on NBC’s Today in 1999. “I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a black kid. I only know what it’s like to grow up as a barber’s son in Saint Paul. I have my own experiences but I got two letters from fathers who said, we understand your problem, but try it anyway. Just go ahead and try it.”

So he did.

And, despite some negative reactions and Schulz’ own doubts, the inclusion of a black character inspired young black readers.

The New York Times revealed a black Army sergeant in Vietnam wrote Schulz about how much it affected him to find “a new character in the strip who shares my name,” while cartoonist Barbara Brandon-Croft still remembers the way it felt when she was 10 years old and saw a black character in the Peanuts strip.

“I remember feeling affirmed by seeing Franklin in ‘Peanuts.’ a little black kid! Thank goodness! We do matter,'” she told the New York Times.

Robb Armstrong was six years old when Franklin was introduced, and it meant so much to him that 20 years later, when he was a cartoonist himself and signed onto the same distributor as Schulz, he asked his editor if he could meet Schulz.

At the time, Armstrong, who created the cartoon strip JumpStart, ended up sending Schulz a JumpStart strip that referenced Charlie Brown’s dog Snoopy.

Armstrong did not meet Schulz until a year and a half after that, according to NPR. When the two finally met, Armstrong was stunned to see that Schulz had framed Armstrong’s comic strip and hung it above his work space.

And later, when Schulz realized Franklin lacked a last name, Schulz asked Armstrong for permission to give his surname to Franklin — which Armstrong called a “tremendous honor” and a “moving” moment.

“He inspired a kid. I don’t think there’s a higher calling in this life,” said Armstrong on NPR’s Weekend Edition. “He inspired some kid 3,000 miles away … it’s incredible what happens when you inspire a kid, and that’s what Schulz did.”

Although the idea of representation sometimes generates controversy or is seen as inconsequential, research shows that children’s self-esteem is indeed affected by mass media and pop culture. Children who lack representation have been found to have lower self-esteem than those with significant representation.

It is, of course, the parents’ duty to ensure their children are strong, confident, and self-assured. But not every child’s home life is positive, and mass media is largely unavoidable, so children are nonetheless impacted by mass media and how it portrays — or doesn’t portray — people.

Providing children with characters, role models, and heroes who look like them builds such children’s confidence, empowering them to imagine their own potential and possibilities. Representation shapes the way people — both children and adults — view themselves.

Moreover, it also shapes the way others view them. Studies show that mass media can serve as an educational tool for people who have little or no direct contact with the person portrayed on the screen; the unfamiliar person is therefore normalized and becomes relatable, providing the viewer with the opportunity to learn more about the person than he or she would have otherwise.

Consider this story, in which a child at the pool reacted positively towards an autistic child — all because she had seen an autistic character on Sesame Street:

The 1960s were among the most difficult and tense periods in American history. When Charlie Brown made a new friend at the beach that day in 1968, the two children — and their creator — broke barriers, bravely promoted tolerance, celebrated interracial friendships, and inspired young readers.

And by demonstrating that together, the white child Charlie and his new black friend Franklin were able to make a bigger and better sandcastle than Charlie Brown was able to make by himself, Schulz made a powerful metaphor from which the world could — and did — learn.

Happy 5oth birthday to Franklin Armstrong.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of any other individual or entity. Follow Sarah on Twitter: @sarahmquinlan.

Posted at 8:00 pm on August 1, 2018 by Sarah Quinlan

https://www.redstate.com/sarahquinl...r-the-story-of-his-creation-debut-and-impact/

Fifty years ago, American cartoonist Charles Schulz introduced his first black character, Franklin, in his beloved and popular Peanuts comic strip.

Perhaps the most moving aspect of Franklin’s debut strip was the immediate simplicity and normalcy of the two boys’ friendship. After Franklin returned Charlie Brown’s lost beach ball to him, the two built a sand castle together, with the pure innocence that only children possess — thus presenting the friendship of a white boy and a black boy as entirely natural and acceptable.

In truth, Franklin made his debut during a time period of widespread racial tension in the United States; he was introduced on July 31, 1968, just months after the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and the violent and deadly riots that followed King’s death.

The idea of Franklin arose, in part, because of King’s death. Just eleven days after King was murdered in April 1968, a white teacher in Los Angeles wrote to Schulz, among other syndicated-strip cartoonists, to urge him to include a black character.

In her letter, Harriet Glickman noted that mass media such as cartoons carry a “tremendous importance in shaping the unconscious attitudes of our kids.” She therefore requested that Schulz introduce a black character in order to “help change those conditions in our society…which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate, and violence”:

Schulz responded within two weeks, telling Glickman he appreciated her suggestion but was concerned about “patronizing” black readers:

Undeterred, Glickman continued to urge integration; during their two months of correspondence, Glickman even included letters from black friends who supported the idea, to assuage Schulz’ fears that he would offend black readers.

One of Glickman’s friends, Kenneth C. Kelly, wrote that a black Peanuts character would both “ease my problem of having my kids seeing themselves pictured in the overall American scene” and “suggest racial amity in a casual day-to-day sense.”

Then, on July 1st, 1968, Schulz told Glickman that a comic strip during the last week of July would be a “first step” regarding the inclusion of a black character.

“I have drawn an episode which I think will please you,” he wrote her.

Glickman’s suggestion and integration campaign had finally succeeded. The Peanuts circle of friends now included a black child.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone liked that the comic strip portrayed a black child among white children.

Schulz admitted he received criticism for depicting Franklin as he would a white child, such as when Franklin and Charlie Brown invited the other to their houses and again when Franklin was pictured sitting in class alongside Peppermint Patty:

There was one strip where Charlie Brown and Franklin had been playing on the beach, and Franklin said, “Well, it’s been nice being with you, come on over to my house some time.” Again, [comic strip newspaper syndication service United Features] didn’t like that.

Another editor protested once when Franklin was sitting in the same row of school desks with Peppermint Patty, and said, “We have enough trouble here in the South without you showing the kids together in school.”

But Schulz wouldn’t back down. He’d previously had to fight to include Bible passages in the 1965 television special A Charlie Brown Christmas, so he was familiar with taking a stand on issues he believed mattered, regardless of who might take offense.

But I never paid any attention to those things, and I remember telling [United Features President] Larry [Rutman] at the time about Franklin—he wanted me to change it, and we talked about it for a long while on the phone, and I finally sighed and said, “Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?”

However, it wasn’t just the negative reactions from white readers and editors that Schulz had to contend with.

Schulz was open about his concerns that, as a white man, he could not write about race properly or adequately capture the black American’s experience. As he had told Glickman, he worried about appearing condescending to black readers.

“I’m not an expert on race, I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a little black boy, and I don’t think you should draw things unless you really understand them,” Schulz said in one interview in 1988.

“I wasn’t sure I can do it frankly,” Schulz said on NBC’s Today in 1999. “I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a black kid. I only know what it’s like to grow up as a barber’s son in Saint Paul. I have my own experiences but I got two letters from fathers who said, we understand your problem, but try it anyway. Just go ahead and try it.”

So he did.

And, despite some negative reactions and Schulz’ own doubts, the inclusion of a black character inspired young black readers.

The New York Times revealed a black Army sergeant in Vietnam wrote Schulz about how much it affected him to find “a new character in the strip who shares my name,” while cartoonist Barbara Brandon-Croft still remembers the way it felt when she was 10 years old and saw a black character in the Peanuts strip.

“I remember feeling affirmed by seeing Franklin in ‘Peanuts.’ a little black kid! Thank goodness! We do matter,'” she told the New York Times.

Robb Armstrong was six years old when Franklin was introduced, and it meant so much to him that 20 years later, when he was a cartoonist himself and signed onto the same distributor as Schulz, he asked his editor if he could meet Schulz.

At the time, Armstrong, who created the cartoon strip JumpStart, ended up sending Schulz a JumpStart strip that referenced Charlie Brown’s dog Snoopy.

Armstrong did not meet Schulz until a year and a half after that, according to NPR. When the two finally met, Armstrong was stunned to see that Schulz had framed Armstrong’s comic strip and hung it above his work space.

And later, when Schulz realized Franklin lacked a last name, Schulz asked Armstrong for permission to give his surname to Franklin — which Armstrong called a “tremendous honor” and a “moving” moment.

“He inspired a kid. I don’t think there’s a higher calling in this life,” said Armstrong on NPR’s Weekend Edition. “He inspired some kid 3,000 miles away … it’s incredible what happens when you inspire a kid, and that’s what Schulz did.”

Although the idea of representation sometimes generates controversy or is seen as inconsequential, research shows that children’s self-esteem is indeed affected by mass media and pop culture. Children who lack representation have been found to have lower self-esteem than those with significant representation.

It is, of course, the parents’ duty to ensure their children are strong, confident, and self-assured. But not every child’s home life is positive, and mass media is largely unavoidable, so children are nonetheless impacted by mass media and how it portrays — or doesn’t portray — people.

Providing children with characters, role models, and heroes who look like them builds such children’s confidence, empowering them to imagine their own potential and possibilities. Representation shapes the way people — both children and adults — view themselves.

Moreover, it also shapes the way others view them. Studies show that mass media can serve as an educational tool for people who have little or no direct contact with the person portrayed on the screen; the unfamiliar person is therefore normalized and becomes relatable, providing the viewer with the opportunity to learn more about the person than he or she would have otherwise.

Consider this story, in which a child at the pool reacted positively towards an autistic child — all because she had seen an autistic character on Sesame Street:

ship | #spnborders | see pinned

@shiphitsthefan

Swim class: "He's silly!" the little girl says, pointing at my kid. "I want to play with him."

"Be gentle," says her grandmother.

"I saw on Sesame Street," and she jumps beside my spinning son.

There's an autistic, nonverbal Muppet. Don't tell me representation doesn't matter.

12:31 PM - Jul 18, 2018

235K

52.8K people are talking about this

The 1960s were among the most difficult and tense periods in American history. When Charlie Brown made a new friend at the beach that day in 1968, the two children — and their creator — broke barriers, bravely promoted tolerance, celebrated interracial friendships, and inspired young readers.

And by demonstrating that together, the white child Charlie and his new black friend Franklin were able to make a bigger and better sandcastle than Charlie Brown was able to make by himself, Schulz made a powerful metaphor from which the world could — and did — learn.

Happy 5oth birthday to Franklin Armstrong.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent those of any other individual or entity. Follow Sarah on Twitter: @sarahmquinlan.