Railing Against the Rich: A Great American Tradition Efforts to limit pay of the wealthiest gained traction in the 1930s; 'economic royalists'

By ALAN BRINKLEY

The Great Depression of the 1930s created hardship and suffering among millions of Americans. It also created populist resentment of elites. Among the many signs of this anger was the astonishing popularity of Huey P. Long, governor of Louisiana and then U.S. senator, a figure so dominant in his own state that his enemies called him a dictator. But to the ordinary people of Louisiana -- and later to millions of ordinary people across the U.S. -- Mr. Long was a heroic figure, fighting for the "common man" and challenging the right of elites to monopolize power and wealth.

Starting in 1933, Mr. Long created a national organization called the "Share Our Wealth Society." He publicized it through his frequent national radio broadcasts (with time provided free by timid network executives), and through his many speeches before many audiences. His goal, he claimed, was a radical redistribution of wealth. Every needy American would receive a "household estate" of $5,000 (almost $80,000 in 2008 dollars), an annual wage of $2,500 ($40,000 in 2008 dollars), and other benefits.

This great boon would be financed by high taxes on people making over $1 million. There would be an $8 million cap, with everything above that confiscated for redistribution. The plan was economically, and probably politically, impossible. But the inability of a wealthy nation to provide jobs and support to millions of citizens made Mr. Long's proposal appealing and persuasive. "Let no one tell you that it is difficult to redistribute the wealth of this land," he told a radio audience in 1934. "It is simple."

Whether or not we are now entering a new Great Depression, we are almost certainly entering a period in which resentment of financial and corporate titans will increase, and in which many politicians will feel they have no choice but to join the chorus of denunciation -- perhaps even a president with almost unprecedented approval ratings as he begins his term. In the 1930s, the popularity of "big business" -- high in the prosperous 1920s -- dropped dramatically, even catastrophically, and did not revive until the corporate world recovered its wealth in World War II.

In the meantime, the wealthy and powerful encountered challenges that make President Barack Obama's $500,000 salary cap on companies seeking federal assistance seem pale by comparison.

Photo by General Photographic Agency/Getty Images)

Huey P. Long

In the 1930s, plans similar to Mr. Long's proliferated and attracted broad support. Francis Townsend, an aging physician in Long Beach, Calif., launched the Townsend Plan, a promise to everyone over 60 of a guaranteed $150 to $200 a month from the government "on condition that they spend the money as they get it." A nationwide "transaction tax" (similar to a V.A.T.) would, he improbably argued, provide enough money to finance the system. Dr. Townsend claimed that he had up to 25 million followers two years after launching his plan -- an unverifiable but not impossible number.

The novelist Upton Sinclair almost won election as governor of California in 1934 by proposing the seizure of idle factories and farms from their capitalist owners. The properties would be managed as cooperatives to give work to the unemployed and to replace the profit system with what he called "production for use." Father Charles Coughlin of Detroit, known as the "radio priest" for his weekly political broadcast, chastised bankers and financiers and demanded a radical inflation of the currency -- an old populist proposal that Father Coughlin insisted would redistribute wealth.

Franklin Roosevelt himself, trying to steal the thunder of the populists, proposed the so-called "soak-the-rich" tax, passed in 1935, which targeted high corporate salaries and investment income, even though it did little to increase government revenues or reduce the real wealth of those required to pay. He made a series of speeches in 1936 excoriating the selfishness and greed of the "economic royalists." He had struggled, he said, "with the old enemies of peace, business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering…. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me, and I welcome their hatred." This polarizing rhetoric was greeted with some of the most enthusiastic responses of any of his speeches.

In the end, this powerful, anti-capitalist populism had relatively little impact on economic life. Mr. Long was assassinated in 1935. Mr. Sinclair lost his election. Father Coughlin and Dr. Townsend joined forces in a third-party presidential challenge in 1936, an effort that received less than 2% of the vote in an election Roosevelt won by a landslide. Few New Deal measures bore any significant relationship to the proposals from these populist movements, although some historians believe that the Townsend Plan helped spur passage of the 1935 Social Security Act.

A few years later, the New Deal abandoned its anti-business rhetoric in the face of a deepening recession. Instead, the government began to embrace Keynesian solutions, which promised economic growth through increased government spending, a strategy that required no significant intrusion into the prerogatives of capitalists.

The Great Depression may not have significantly weakened the power and wealth of the "economic royalists," but the animus toward them was not without consequences. The utilities magnate Samuel Insull fled the country to avoid prosecution for fraud, only to be extradited back to the U.S. to stand trial, where he was marched in and out of court in handcuffs. (He was ultimately acquitted.)

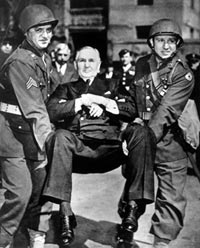

Sewell Avery, the president of Montgomery Ward, was carried out of his office by police during a 1944 labor dispute; a photograph of the event was one of the most widely published in the nation. There was a special gleefulness among much of the public in seeing once-powerful titans fall, as many of them did. Even those who flourished bridled at the rhetoric used against them.

Sewell Avery, the president of Montgomery Ward, was carried out of his office by police during a 1944 labor dispute; a photograph of the event was one of the most widely published in the nation. There was a special gleefulness among much of the public in seeing once-powerful titans fall, as many of them did. Even those who flourished bridled at the rhetoric used against them.

As late as 1940, 11 years after the Depression began, images of brutal and greedy capitalists remained staples of popular culture. John Steinbeck's 1939 novel "The Grapes of Wrath," and the John Ford film adaptation a year later, were great popular successes, not despite but because of their harsh denunciations of capitalists and their flunkies. Tom Joad, a young man politicized by the Depression, leaves his family after killing a strikebreaker (an act neither Steinbeck nor Ford condemned), but not before making a classically radical-populist prophecy: "Wherever there's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there…. An' when our folks eat the stuff they raise an' live in the houses they build -- why I'll be there."

Few 21st-century Americans have any real experience with economic populism. That appears to be changing fast. In the 1930s, the demonization of the upper class did not really begin until almost two years after the stock-market crash.

We are now six months into our own economic crisis, and signs of populist resentment are already visible: in the perverse fascination with Bernard Madoff's remarkable fraud, the popular outrage at the tax problems of public officials, the growing contempt for the many overseers of the credit markets, the ruined investments of millions of ordinary people, the growing army of the unemployed (still far below the 15% to 25% unemployment of the 1930s, but 7.6% in January and growing fast), the likelihood of a recession that could last not just for months, but for years.

These are the preconditions of populist revolts. Mr. Obama's chastise-ments of bankers and CEOs have been relatively mild compared to the routine denunciations of "economic royalists" in the 1930s. But the longer the crisis goes on and the deeper it grows, the more Huey Long-like challenges to those in power will arise, and the more pressure there will be for national leaders to launch populist battles of their own.

Whether that would help or hurt the Obama administration is hard to predict. In 1896, in the midst of another great depression, the Democratic party chose as its candidate the great populist hero William Jennings Bryan. His crushing defeat ushered in 36 years of almost unbroken Republican rule. In 1936, at the height of Franklin Roosevelt's populist rhetoric, his landslide re-election helped solidify a comparable period of Democratic dominance.

Cultural populism has been a staple of the right since at least 1968, and it has alternately helped, and badly hurt, conservative candidates and causes.

Economic populism has the same capacity either to bring down the president's ambitious agenda or, if handled skillfully, to open up opportunities for greater change than he may yet have imagined.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123396621006159013.html

By ALAN BRINKLEY

The Great Depression of the 1930s created hardship and suffering among millions of Americans. It also created populist resentment of elites. Among the many signs of this anger was the astonishing popularity of Huey P. Long, governor of Louisiana and then U.S. senator, a figure so dominant in his own state that his enemies called him a dictator. But to the ordinary people of Louisiana -- and later to millions of ordinary people across the U.S. -- Mr. Long was a heroic figure, fighting for the "common man" and challenging the right of elites to monopolize power and wealth.

Starting in 1933, Mr. Long created a national organization called the "Share Our Wealth Society." He publicized it through his frequent national radio broadcasts (with time provided free by timid network executives), and through his many speeches before many audiences. His goal, he claimed, was a radical redistribution of wealth. Every needy American would receive a "household estate" of $5,000 (almost $80,000 in 2008 dollars), an annual wage of $2,500 ($40,000 in 2008 dollars), and other benefits.

This great boon would be financed by high taxes on people making over $1 million. There would be an $8 million cap, with everything above that confiscated for redistribution. The plan was economically, and probably politically, impossible. But the inability of a wealthy nation to provide jobs and support to millions of citizens made Mr. Long's proposal appealing and persuasive. "Let no one tell you that it is difficult to redistribute the wealth of this land," he told a radio audience in 1934. "It is simple."

Whether or not we are now entering a new Great Depression, we are almost certainly entering a period in which resentment of financial and corporate titans will increase, and in which many politicians will feel they have no choice but to join the chorus of denunciation -- perhaps even a president with almost unprecedented approval ratings as he begins his term. In the 1930s, the popularity of "big business" -- high in the prosperous 1920s -- dropped dramatically, even catastrophically, and did not revive until the corporate world recovered its wealth in World War II.

In the meantime, the wealthy and powerful encountered challenges that make President Barack Obama's $500,000 salary cap on companies seeking federal assistance seem pale by comparison.

Photo by General Photographic Agency/Getty Images)

Huey P. Long

In the 1930s, plans similar to Mr. Long's proliferated and attracted broad support. Francis Townsend, an aging physician in Long Beach, Calif., launched the Townsend Plan, a promise to everyone over 60 of a guaranteed $150 to $200 a month from the government "on condition that they spend the money as they get it." A nationwide "transaction tax" (similar to a V.A.T.) would, he improbably argued, provide enough money to finance the system. Dr. Townsend claimed that he had up to 25 million followers two years after launching his plan -- an unverifiable but not impossible number.

The novelist Upton Sinclair almost won election as governor of California in 1934 by proposing the seizure of idle factories and farms from their capitalist owners. The properties would be managed as cooperatives to give work to the unemployed and to replace the profit system with what he called "production for use." Father Charles Coughlin of Detroit, known as the "radio priest" for his weekly political broadcast, chastised bankers and financiers and demanded a radical inflation of the currency -- an old populist proposal that Father Coughlin insisted would redistribute wealth.

Franklin Roosevelt himself, trying to steal the thunder of the populists, proposed the so-called "soak-the-rich" tax, passed in 1935, which targeted high corporate salaries and investment income, even though it did little to increase government revenues or reduce the real wealth of those required to pay. He made a series of speeches in 1936 excoriating the selfishness and greed of the "economic royalists." He had struggled, he said, "with the old enemies of peace, business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering…. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me, and I welcome their hatred." This polarizing rhetoric was greeted with some of the most enthusiastic responses of any of his speeches.

In the end, this powerful, anti-capitalist populism had relatively little impact on economic life. Mr. Long was assassinated in 1935. Mr. Sinclair lost his election. Father Coughlin and Dr. Townsend joined forces in a third-party presidential challenge in 1936, an effort that received less than 2% of the vote in an election Roosevelt won by a landslide. Few New Deal measures bore any significant relationship to the proposals from these populist movements, although some historians believe that the Townsend Plan helped spur passage of the 1935 Social Security Act.

A few years later, the New Deal abandoned its anti-business rhetoric in the face of a deepening recession. Instead, the government began to embrace Keynesian solutions, which promised economic growth through increased government spending, a strategy that required no significant intrusion into the prerogatives of capitalists.

The Great Depression may not have significantly weakened the power and wealth of the "economic royalists," but the animus toward them was not without consequences. The utilities magnate Samuel Insull fled the country to avoid prosecution for fraud, only to be extradited back to the U.S. to stand trial, where he was marched in and out of court in handcuffs. (He was ultimately acquitted.)

As late as 1940, 11 years after the Depression began, images of brutal and greedy capitalists remained staples of popular culture. John Steinbeck's 1939 novel "The Grapes of Wrath," and the John Ford film adaptation a year later, were great popular successes, not despite but because of their harsh denunciations of capitalists and their flunkies. Tom Joad, a young man politicized by the Depression, leaves his family after killing a strikebreaker (an act neither Steinbeck nor Ford condemned), but not before making a classically radical-populist prophecy: "Wherever there's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there…. An' when our folks eat the stuff they raise an' live in the houses they build -- why I'll be there."

Few 21st-century Americans have any real experience with economic populism. That appears to be changing fast. In the 1930s, the demonization of the upper class did not really begin until almost two years after the stock-market crash.

We are now six months into our own economic crisis, and signs of populist resentment are already visible: in the perverse fascination with Bernard Madoff's remarkable fraud, the popular outrage at the tax problems of public officials, the growing contempt for the many overseers of the credit markets, the ruined investments of millions of ordinary people, the growing army of the unemployed (still far below the 15% to 25% unemployment of the 1930s, but 7.6% in January and growing fast), the likelihood of a recession that could last not just for months, but for years.

These are the preconditions of populist revolts. Mr. Obama's chastise-ments of bankers and CEOs have been relatively mild compared to the routine denunciations of "economic royalists" in the 1930s. But the longer the crisis goes on and the deeper it grows, the more Huey Long-like challenges to those in power will arise, and the more pressure there will be for national leaders to launch populist battles of their own.

Whether that would help or hurt the Obama administration is hard to predict. In 1896, in the midst of another great depression, the Democratic party chose as its candidate the great populist hero William Jennings Bryan. His crushing defeat ushered in 36 years of almost unbroken Republican rule. In 1936, at the height of Franklin Roosevelt's populist rhetoric, his landslide re-election helped solidify a comparable period of Democratic dominance.

Cultural populism has been a staple of the right since at least 1968, and it has alternately helped, and badly hurt, conservative candidates and causes.

Economic populism has the same capacity either to bring down the president's ambitious agenda or, if handled skillfully, to open up opportunities for greater change than he may yet have imagined.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123396621006159013.html